Hyperopia: definition, symptoms, and treatment

Hyperopia (also known as farsightedness or hypermetropia) is caused by an eye that is too short or by insufficient refractive power of the eye’s optical system. This visual disorder affects nearly 15% of the population and can be managed with corrective lenses or surgery.

Learn more about other vision issues

Myopia

Astigmatism

Presbyopia

What is hyperopia?

Mechanisms and symptoms

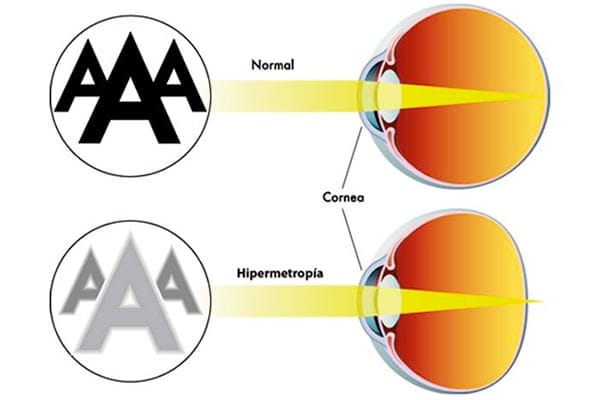

A healthy eye focuses images precisely on the surface of the retina. When this does not occur, visual disturbances arise. Hyperopia occurs when images are formed behind the retinal plane. Near vision is systematically impaired, and depending on the degree of hyperopia, some patients may also experience difficulty seeing at a distance.

This defect is often diagnosed late because affected individuals tend to compensate naturally by constantly accommodating—using the eye’s lens to adjust focus. However, this accommodative ability diminishes with age, making hyperopia more noticeable over time.

Continuous accommodative effort frequently leads to headaches (cephalalgia), visual fatigue, and ocular redness. These symptoms should prompt patients to seek an ophthalmological consultation as soon as possible.

Early management of hyperopia is particularly important in children to prevent learning delays and serious medical complications, such as strabismus or amblyopia (disorders in the development of visual function). In adults, untreated hyperopia can also lead to more serious conditions, especially glaucoma.

Degrees of hyperopia

Hyperopia is measured in diopters (D):

- Mild hyperopia: between +1 and +2 D

- Moderate hyperopia: between +2 and +4 D

- High hyperopia: above +4 D

Mild to moderate hyperopia

A mildly hyperopic eye may not always have blurred near vision, especially in young patients. In hyperopia, light rays focus behind the retina. Accommodation brings this focus forward onto the retina, allowing clear vision without optical correction. However, this constant effort can cause headaches and visual fatigue, especially after prolonged near work or computer use.

For young adults with mild hyperopia who experience headaches or visual fatigue, glasses may be prescribed—not to improve vision per se, but to relieve the need for constant accommodation and thus reduce discomfort. Glasses are especially helpful for near tasks, while distance vision may remain comfortable without correction.

Mild hyperopia after age 45

After age 45, everyone develops presbyopia, a loss of accommodative ability. Hyperopic patients then begin to experience blurred vision without glasses and will require correction for distance vision around age 55.

High or severe hyperopia

High hyperopia (greater than 3 diopters) appears in childhood and can cause strabismus or amblyopia if not corrected early. Highly hyperopic adults may experience complications due to the small size of the eye, such as a narrow iridocorneal angle, increasing the risk of angle-closure glaucoma. In extreme cases, when the eye is very small, this is called microphthalmia or even nanophthalmia (axial length less than 20 mm), which is a congenital condition.

Evolution of hyperopia

A hyperopic eye is anatomically small and cannot shrink further; therefore, hyperopia cannot worsen. The eye may remain the same size (stable hyperopia) or grow, which reduces hyperopia and improves vision. In some cases, especially during childhood or adolescence, the eye may grow excessively, converting hyperopia into myopia.

If your ophthalmologist increases your hyperopic prescription, it is not because your hyperopia has worsened, but because your accommodative capacity has decreased.

Mild hyperopes will need glasses around age 40, and the strength of the correction will need to be increased over time as accommodation declines.

Hyperopia can coexist with other vision disorders, such as astigmatism or presbyopia, but it cannot coexist with myopia, as the eye cannot be both too small and too large at the same time.

Causes and risk factors

To focus images on the retina, two factors must be perfectly matched: the refractive power provided by the cornea and lens, and the distance light travels through the eye to the retina.

Hyperopia thus has two possible anatomical causes:

- An eye that is too short (insufficient axial length)

- Insufficient refractive power (cornea and/or lens too flat)

Young children are naturally hyperopic due to the small size of the eye at birth. As the eye grows during early childhood, hyperopia usually resolves. When it persists, often due to hereditary factors, it does not worsen, but presbyopia may make it more noticeable later in life.

How is hyperopia treated?

Hyperopia can be corrected in three ways: glasses, contact lenses, or refractive surgery. The choice depends on clinical examination and patient preference.

Correction with glasses and contact lenses

Hyperopia is corrected using convex (plus) lenses, which are thicker at the center. Depending on the patient, correction may be needed all the time or only for reading or screen work. Glasses may be considered unaesthetic by some because they magnify the eyes, in which case contact lenses are an alternative. Both are covered by national health insurance, unlike refractive surgery, which is considered elective.

Refractive surgery for hyperopia

Laser refractive surgery is a common option for hyperopic patients. Techniques include LASIK, SMILE, and PRK, all of which reshape the cornea to increase the eye’s refractive power, allowing images to focus on the retina.

These procedures are painless, performed under local anesthesia in an outpatient setting, and usually restore clear vision within a few days. The choice of technique depends on corneal thickness and the patient’s lifestyle. LASIK, for example, requires sufficient corneal thickness and is less suitable for those at risk of eye trauma due to the creation of a corneal flap.

Correction with phakic lens implants

For high hyperopia, where laser surgery would require excessive corneal tissue removal, intraocular lens implants may be considered. Phakic lens implants (placed between the iris and the lens) are additive and reversible, suitable for hyperopia up to 10 diopters. For older patients or those with cataracts, lens replacement surgery (removal of the natural lens and implantation of an artificial one) is preferred, as it also addresses lens opacification.

Frequently asked questions

Can hyperopia coexist with presbyopia or other vision disorders?

Yes, hyperopia can coexist with presbyopia and astigmatism, but not with myopia.

Can hyperopia be corrected with implants?

Yes, especially for high hyperopia or when laser surgery is not suitable. Options include phakic lens implants or lens replacement, depending on age and ocular health.

Does wearing glasses influence the progression of hyperopia?

No, wearing glasses does not affect the anatomical development of the eye, especially in adults. The goal is to provide comfort and prevent complications such as amblyopia in children.

Book an appointment with Dr. Rambaud

Have a question? Ask Dr. Rambaud

This page was written by Dr. Camille Rambaud, an ophthalmologist based in Paris and a specialist in refractive surgery.

0 Comments